The Counterintuitive Way Musicians Achieve Greatness (and How You Can Too)

Photo by Vadim Artyukhin on Unsplash

Confessions of an Elite Musician

In the early 1990s, a study of violin players at Universität der Künste tried to find out what separated the elite ones from the average players.

To do this, they did a series of interviews and asked the musicians to record their days. Without data, it’s easy to assume that the elite players likely spend more time on music. That they sacrifice their weekend outings and family gatherings to get better at their craft.

But the data had a peculiar and disparate story to tell.

First of all, it was made clear that the elite players and the average ones spent the same number of hours practicing music (~50 hours/week). Clearly, you just can’t ‘hustle’ your way out of things.

So why were the elites better? Two reasons:

- Even though both groups practiced for the same amount of time, the elite ones spent almost 3 times more hours on deliberate practice — the kind of practice that is uncomfortable, tough, and aimed at improving weaknesses.

- The second difference was in the manner of scheduling. The elite players scheduled their work in 2 rigid sessions — one in the morning and one in the afternoon. The average players, on the other hand, spent almost all their waking hours practicing in a haphazard manner spread throughout the day.

By doing this, they drew clear boundaries between work and leisure. As a result, the elite players were not only good at their craft, but also the most relaxed of all.

Further, these are not just findings of a study of a few violin players. This pattern is found across numerous fields. Consider this.

A piano player, let’s call him Jeremy, confessed to Cal Newport, (the pioneer of Deep Work), about his surprisingly relaxed life as compared to other struggling players. He then went on to explain what he did differently.

There’s a lot we can learn from his confession so let’s dissect his advice.

Strategy #1: Avoid Flow. Do What Does Not Come Easy.

“The mistake most weak pianists make is playing, not practicing. If you walk into a music hall at a local university, you’ll hear people ‘playing’ by running through their pieces. This is a huge mistake. Strong pianists drill the most difficult parts of their music, rarely, if ever playing through their pieces in entirety.”

Strategy #2: To Master a Skill, Master Something Harder.

“Strong pianists find clever ways to ‘complicate’ the difficult parts of their music. If we have a problem playing something with clarity, we complicate it by playing the passage with alternating accent patterns. If we have problems with speed, we confound the rhythms.”

Strategy #3: Systematically Eliminate Weakness.

“Strong pianists know their weaknesses and use them to create strength. I have sharp ears, but I am not as in touch with the physical component of piano playing. So, I practice on a mute keyboard.”

Is Flow The Opiate of the Mediocre?

These findings can be surprising at first. To many creatives, flow is their God. Everyone loves the feeling of being lost in what they’re doing and coming out on the other side with a phenomenal piece of art.

I’ve been in flow. I get it. But, flow isn’t necessarily going to push us further. Let me explain why.

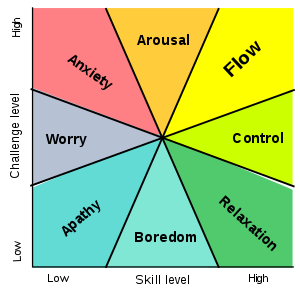

Source, royalty-free.

Look at the graph above. It shows the right challenge-skill ratio you need to enter a flow state. If your skill is higher than the challenge, it’ll be too easy. If your challenge is higher than your skill level, it will be challenging.

Naturally, both these states will trigger thoughts and emotions in your mind. You’ll either think “Oh this is too easy. I’m bored!” or “I just can’t seem to get it. I think I should watch Netflix instead!”

When the ratio is “just right” you enjoy whatever you’re doing without getting bored or anxious. As I said, this state feels great. As I write this article, I may be close to entering that state (though the act of calling it out like this may snap me out of it!)

By definition, if you follow the challenge-to-skill ratio, you’ll always do something close to your comfort zone — a little outside, but still, close.

Again, writing this article doesn’t make me uncomfortable. It isn’t hard. I write every morning and have done it hundreds of times. But the question we should ask is, “Am I improving?”

Maybe. But only marginally. For the most part, I’m not learning new things about writing or mastering a sub-skill that I suck at. I’m just writing about a topic that interests me. Just like those piano players who keep practicing what they already know.

To really grow as a writer, I need to learn a variety of skills like copywriting, persuasion, writing introductions that hook people, transitions, open loops, and whatnot.

Until I do those things, I’m not growing. And thus, if I keep chasing flow, my growth will be too slow, if any.

So What’s the Alternative?

When you learn a new skill, everything is hard. As you start to master little sub-skills, you grow exponentially. Soon you reach a point where you know enough about the skill to enjoy doing it.

Let me give you an example. As I’ve picked up the guitar last week, everything seems hard. My fingers hurt, playing chords is tough, changing chords is tougher, and it will likely take a couple of weeks to play a song.

But once I reach that level, I have two choices — to keep playing the songs in my repertoire or to push the limits of my skill by chasing the hard things.

Most people choose the first option because it’s easy and it’s fun. Perhaps they can enter a state of flow as well. But this is also where their learning curve starts to flatten.

Let’s take an example from sports. Imagine you’re a basketball player. There are two choices you have when it comes to practice.

First — you can play a game with your friends and get to have fun. The game is going to improve your skills. It may also lead you to achieve a flow state.

Second — you can practice your free throws with a coach and a camera. Every 10 minutes you look at the camera and find the cause behind missed shots — too long, too short, left, right, etc. Then you review your shortcomings and try to fix them in the next round. You will not be in flow. It will be hard. But your skill will improve.

The reason behind this apparent debate between flow and deliberate practice is that their purpose is different. Flow puts us in a happy state where we can surely get lots of things done.

The aim of deliberate practice, however, isn’t to make you happy. It’s to improve. And so it’s hard. But the skill gains are worth the effort.

Learn to Balance the Two

I’m not telling you to let go of activities that get you into flow. Chase flow — it feels good! But at the same time, set aside time for deliberate practice. Consciously try to improve the things you suck at. That’s going to break your plateaus and unlock growth.

Coming back to my writing, I think I need to study more articles and styles of great writers. I need to know how to persuade with the written word. How to edit and cut the fat. How to improve my vocabulary. And a hundred other sub-skills I need to get good at.

This will not happen automatically if I just keep posting articles. No. I have to consciously work on them.

Does that mean that I won’t be able to write as much or be in flow? Yes. But that also means that my writing will be better. That’s a trade-off I’m willing to make.

In your own life, see how you can apply more deliberate practice to improve your weaknesses. No matter your area of interest, you can break it down and consciously tackle the hard things.

The good thing is that if you practice deliberately, you don’t have to put in as many hours as others. So be like a sprinter — go all-in and then relax to do it again the next day. And the next day. And the next. Until you’re finally done.

Sorry, I’m kidding. You’re never “done.” Because as long as you live, you need to grow. And that growth is your only reward.